Mahjong goes to London

It’s a regularly stated fact that it was the American entrepreneur Joseph Park Babcock who first commercially exported mahjong from China in 1920, after it was popularised amongst the expatriate community in Shanghai. But what do we know about the game’s arrival in Europe?

Mahjong historians have found that the earliest known set of tiles resembling current day mahjong was made in 1873 and that the popularity of the game blossomed after the fall of the Qing Empire in 1911. No longer confined to the intellectual elite, play became visible not only to ordinary people but to the foreign expatriates living in Shanghai. Introduced into the many clubs that served that community by either an Englishman or an American (accounts differ), it’s popularity prompted Mr Babcock to commission the manufacture and shipment of sets he trademarked as “Mah-jongg " and to write a set of rules in English.

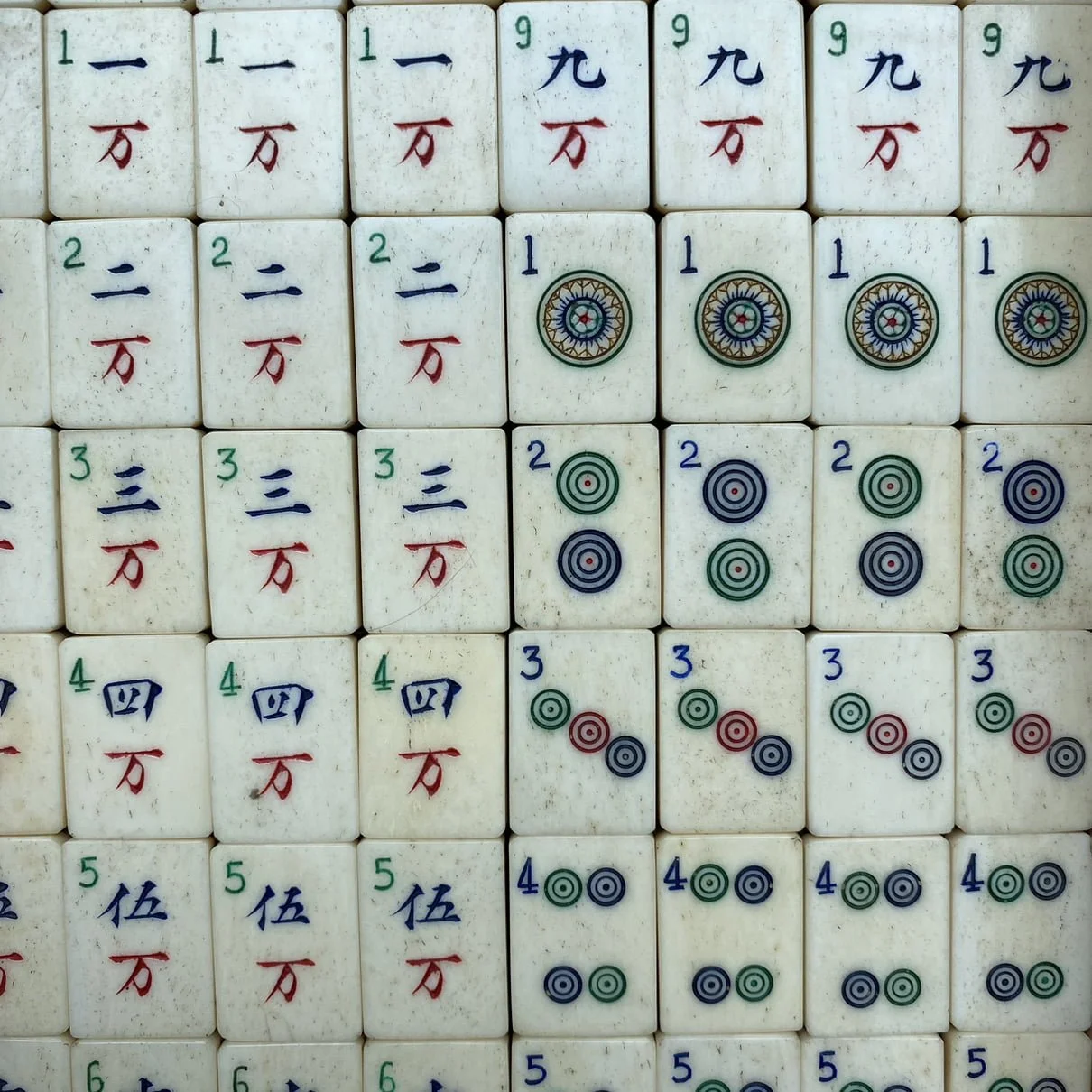

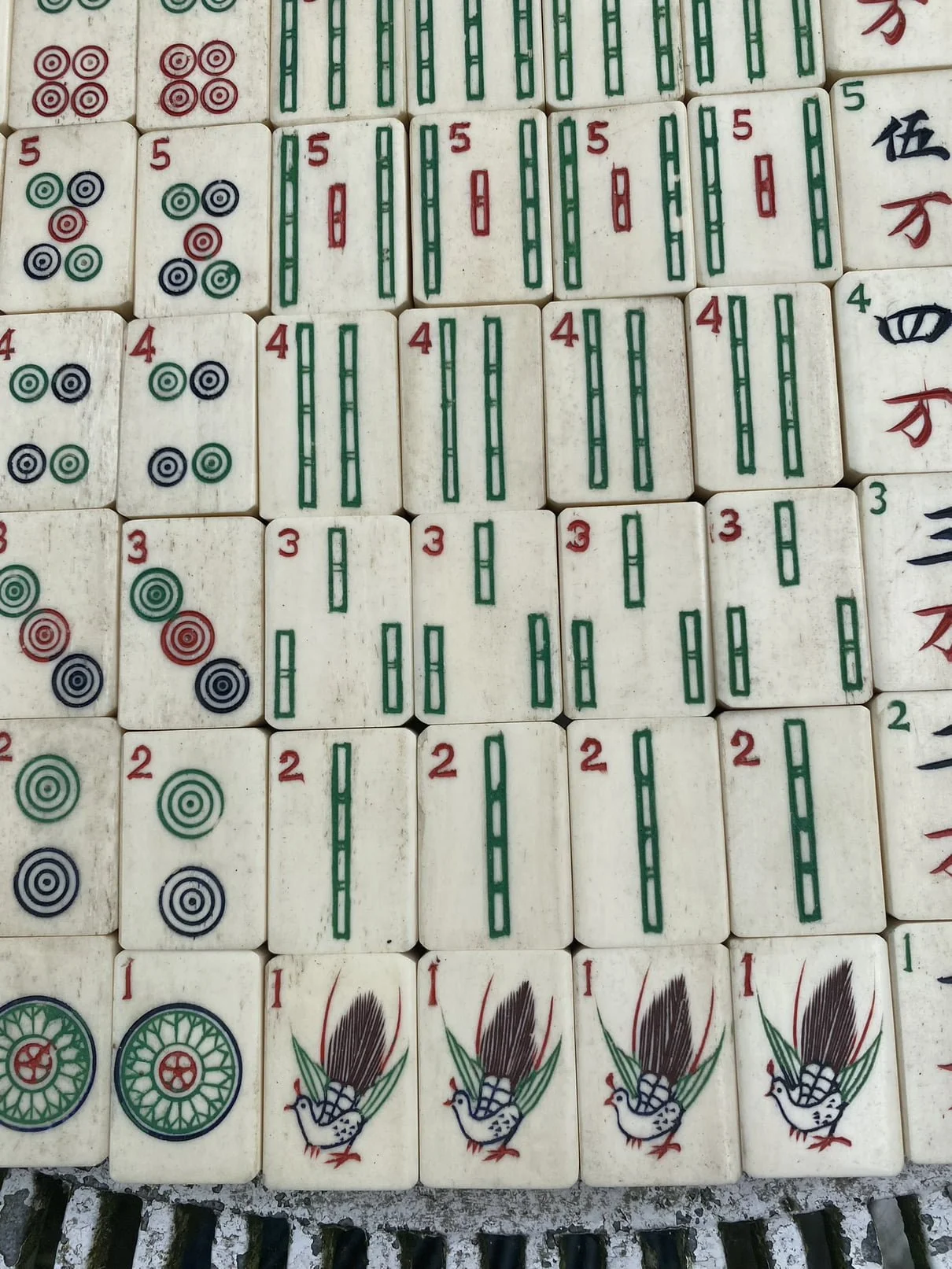

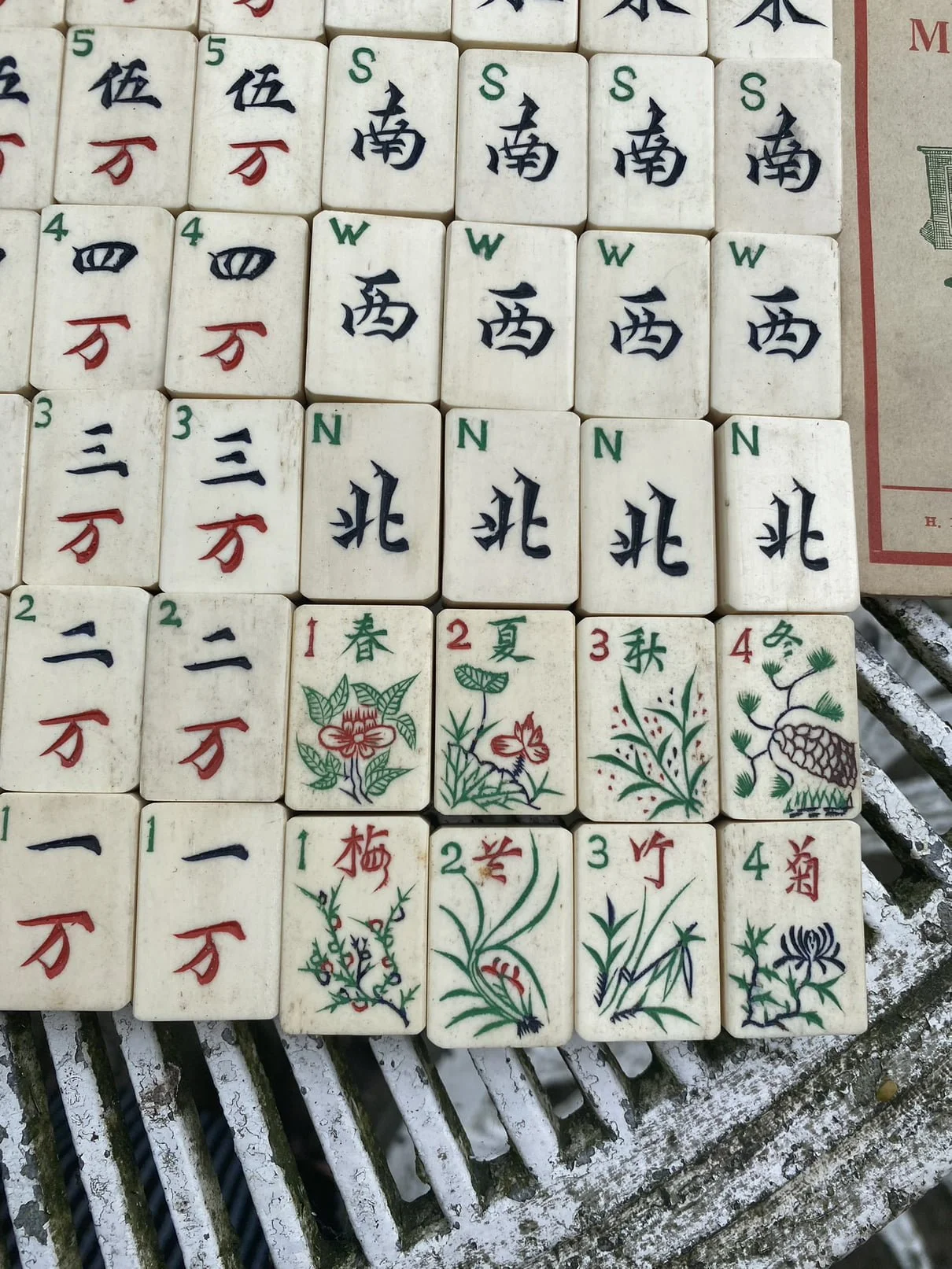

To make the sets marketable in America the tiles had letters or numbers added to their corner to ease recognition. This idea is generally, but not universally, attributed to Babcock. The first commercial shipment of sets to America was in October 1920 and it didn’t take long for the craze to take hold there or to appear in Britain and many parts of the Empire, especially India and Hong Kong. Rules for the game were not universal and each country, often each manufacturer, developed it’s own peculiarities. By 1923 the British games manufacturer Chad Valley was producing its own range of sets, with its own rulebook. The most popular rules in Britain quickly became The Queen’s Club Rules and those contained in a pamphlet by CMW Higginson, both of which were variations on Shanghai rules rather than an adoption of Babcock’s simplification.

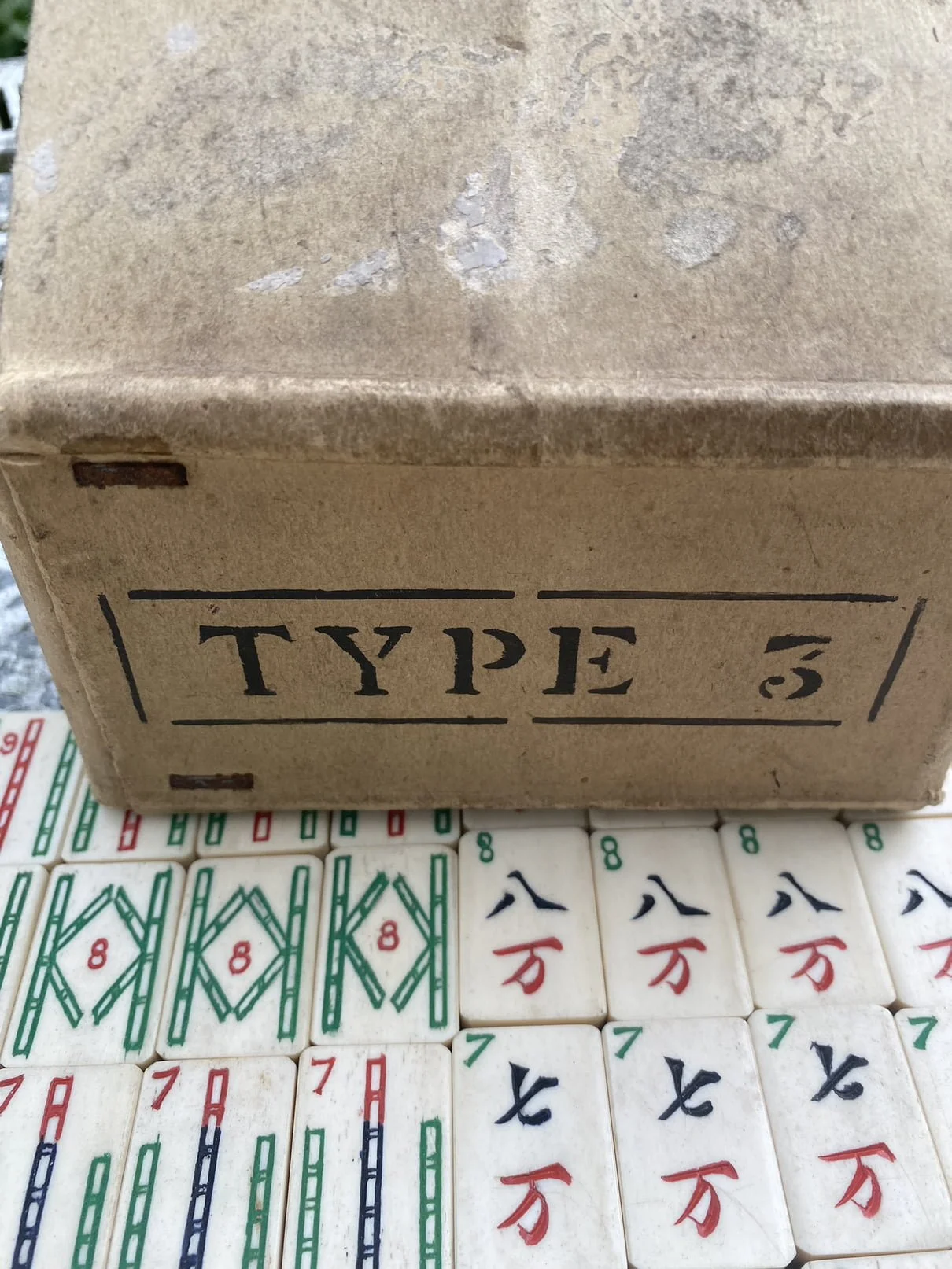

After the mahjong craze took off American and British entrepreneurs set up large workshops in Shanghai, often importing small family workshops from Ningbo, Anhui and Zhejiang to work alongside each other in a more efficient and productive system. The process of manufacture was organised into a production line, with each person completing their own speciality on each set. In some cases the wood cabinets were also made in China, but as production became more streamlined British companies would take advantage of the skills only available in China (making and decorating the tiles) and have the tiles shipped in strong cardboard boxes, then pack them into British made wood cabinets after import.

Manufacturers would produce different sets with a different price tag. Differences extended to the thickness of the bone, the intricacy of the carving, the number of extra ‘flower and season’ tiles, the type of material from bone and bamboo to all bamboo to hand-carved plastic. This set, unused, was found by us in its original shipping box, labelled ‘Type 3’ and shipped by Harvie Goode & Co., Merchants and Commission Agents, Shanghai. The name of the workshop doesn’t appear, but Harvie, Goode & Co is mentioned in Men of Shanghai and North China, 1935 edition.

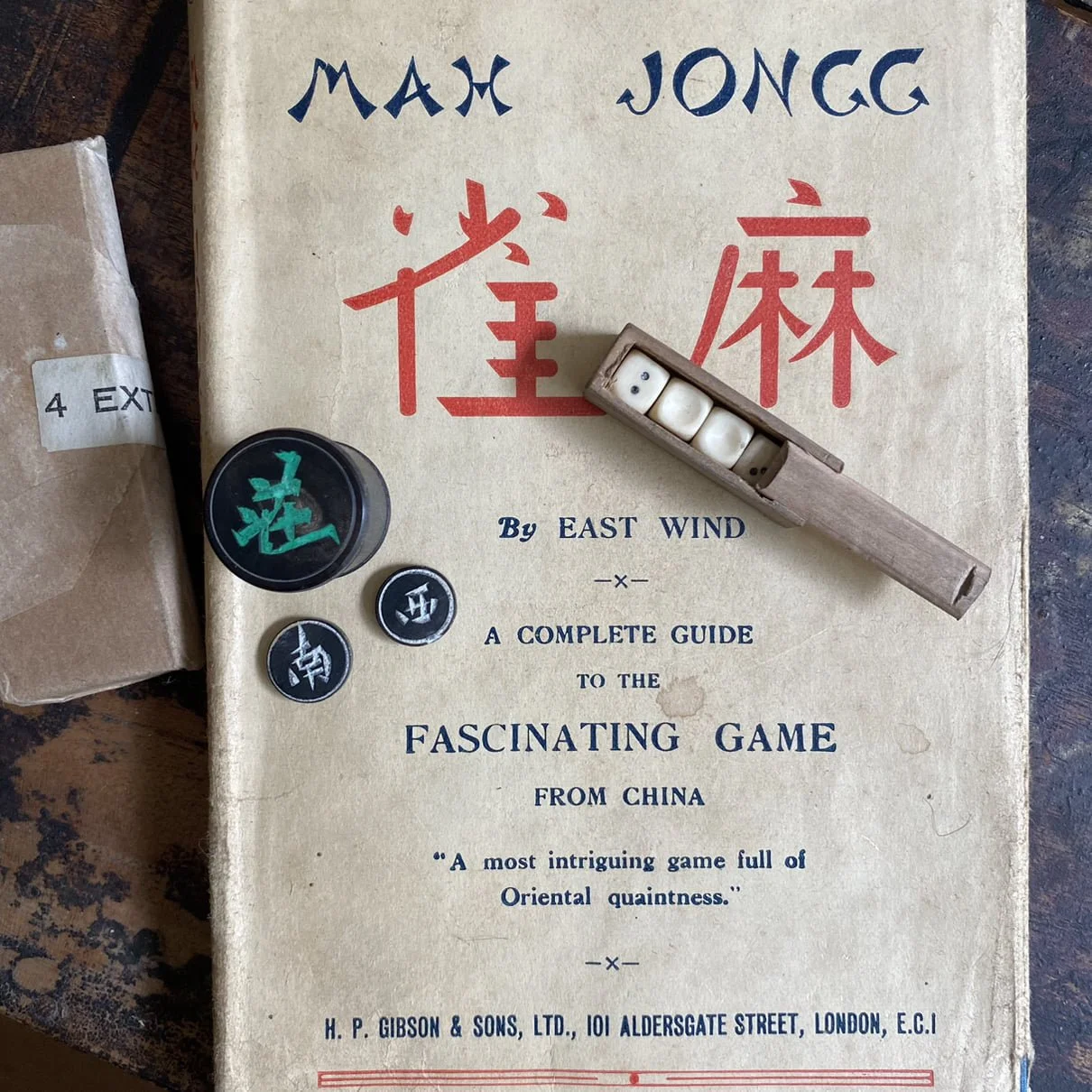

The rule book included inside the box was a very popular publication, printed in 1923, by the games manufacturer H.P. Gibson & Sons Ltd.

In 1923, in London, the bar man at the Savoy created a mahjong cocktail and mahjong sets outsold radio sets in the same price range, even though radios were considered the principal source of home entertainment. The craze settled down as the decade reached its end. Challenged by the upswing of Bridge, mahjong still remained a popular game in England until the Second World War, after which sets emerged made from polystyrene, thick cardboard and wood composite with stamped or painted decoration, made in England.

H. P. Gibson’s catalogue, 1924 (note: £15 is around £800 in today’s economy)